The Case for Geriatric Liaison Services in Surgery

How can we improve health outcomes for an aging population? Strategic Advisory Consultant Jordan Pilipavicius reflects on his own experiences in clinical practice while exploring the evidence surrounding the use of geriatric liaison pathways for elderly and frail patients who are undergoing surgery.

The challenge of managing older patients within surgery cannot be understated: the percentage of older persons undergoing surgery is increasing and is predicted to increase further still.¹

In the UK, there are a greater number of older people than ever before and the number continues to grow: over-65s accounted for 16.4% of the total population at the time of the 2011 census, by 2021 this had grown to 18.6%.

Disproportionately, over-65s account for 43.2% of all hospital admissions in England, according to NHS Digital data², and a 2019 study examining the age profiles of patients undergoing surgical procedures in England reported that 22.9% of over-75s had undergone a surgical procedure in 2015 – an increase of 8% from 1999.³

While increases in mortality, post-operative complications and increased post-surgical length of stay⁴ may be somewhat expected with this patient cohort, as a result advancing age, the evidence suggests that we can do better to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes for frail patients.

Benefits of a geriatric liaison service

Looking back at my time as a junior member of the general surgery team at a trust in the north of England, frail patients admitted under surgery were one of the more challenging cohorts to manage. Often, this was not due to surgical complications, which the senior surgical team were accustomed to dealing with, but due to medical complications arising during their admission.

Of course, medical colleagues were always on hand, if needed, to give advice or review a patient – but this would typically be on an ‘as and when required’ basis, from the already stretched on-call medical registrar. Given the frequent rotation of on-call medical personnel, there was little continuity of care using this approach. My colleagues and I felt that if continuity of care was established through regular review, by a physician embedded as part of the service, these patients could be more effectively and efficiently treated, in some cases even avoiding the necessity for a medical review altogether, through pre-emptive management.

I saw the benefits of this method first-hand, when cross-covering with orthogeriatric colleagues, as this approach is already well established in orthopaedics across the UK. While there are variations in orthogeriatric models of care in operation, the service generally takes a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) approach to optimising frail trauma patients, with elderly care physician input to ensure patients are medically optimised, both before and after surgery.

The concept of a geriatric liaison service is still, however, to be more widely adopted by other surgical specialties, despite it potential benefits for both patients and providers.

Improving patient and operational outcomes

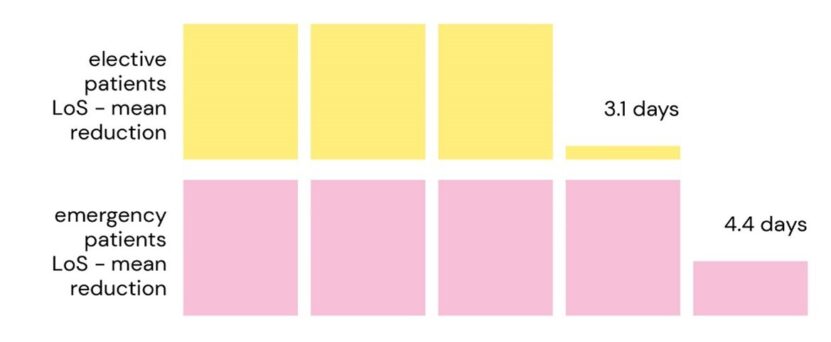

A 2018 study piloted a liaison service for patients admitted on an elective and an emergency basis for gastrointestinal surgery at a UK NHS Trust.⁵ The intervention consisted of implementing a pre-operative comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) clinic for elective patients, in addition to twice weekly geriatrician inpatient ward rounds and twice weekly MDT discharge planning meetings for both elective and emergency patients. The service had no minimum age limit, with open access referrals accepted from surgeons, anaesthetists, nursing and therapy staff. A geriatrician-led surgical rehabilitation ward was also utilised for patients with ongoing medical complications and rehabilitation needs.

The study concluded the intervention was responsible for a mean reduction in length of stay (LOS), for patients over-60, of 3.1 days and 4.4 days for elective and emergency patients respectively – a source of potentially significant cost savings for providers, in addition to improving flow through the hospital.

Similar results were observed in trials implementing a geriatric liaison service in urology; a 2019 study reported a reduction in LOS of 19%. Furthermore, the urology trial not only showed benefits for the provider, but also for patients – with a reported lower incidence of postoperative complications following implementation of the service.⁶

Financial Case for Geriatric Liaison

In terms of economic viability – the 2018 study⁵ estimated that potential savings from reduced lengths of stay could equate to approximately £300,000 a. for the Trust in which study took place (when taking confidence intervals into account this could range between £75,000 to £590,000). While the authors of the study used NHS quality improvement methodology to arrive at these figures, they acknowledge that this analysis is simplistic, but it does give a high-level estimate of the potential savings associated with the service.

From a resourcing perspective, the service required four programmed activities (PAs) of consultant time. Even at the top end of the consultant pay scale for the 2003 contract, this would equate to £47,653 p.a. to resource the service (excl. pension contribution and NICs). This demonstrates that this service could not only improve patient outcomes, but also save money for Trusts, at a time when finances remain increasingly challenging.

Best Practice Guidance

The liaison approach is advocated by relevant professional bodies in both gerontology and perioperative care. In response to the relationship between frailty and adverse surgical outcomes, the Centre for Perioperative Care and the British Geriatric Society produced a joint guidance document⁷, a key recommendation from which is establishing a perioperative Frailty Team with expertise in comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) to provide clinical care throughout the patient pathway.

Changing your services for frail surgical patients

The concept of a geriatric liaison service is just one small piece of the puzzle, in terms of the steps that healthcare providers can make to optimise care for frail patients within the wider healthcare system. It is widely acknowledged that older people admitted to hospital are at increased risk of deconditioning due to extended hospital admissions – with a 2020 meta-analysis estimating a prevalence in hospital associated disability of 30% amongst people aged 65 and over admitted to hospital.⁸ Other initiatives such as frailty same day emergency care (SDEC) units are rapidly gaining traction , and alternative pathways to avoid or minimise the time these patients spend in hospital are increasingly being considered and implemented.

At the same time, the concept of optimising peri-operative care need not be limited to frail patients; it can be applied to all those requiring elective procedures, especially those with multiple co-morbidities/complexity requiring greater peri-operative input or more intensive ‘pre-habilitation’ prior to their procedure. The NIHR, RCoA and Macmillan, for example, have produced clear pre-habilitation care principles for cancer patients⁹ requiring surgical intervention. The Scottish Government has also produced practical guidance for implementing pre-habilitation services for cancer patients, as part of a growing push to implement this service across Scotland.¹⁰

The onus, however, of perioperative care and patient optimisation should not rest solely on secondary care. Building on this concept, interventions such as the one described in the article are often implemented at specialty level – i.e. a geriatric liaison service for a specific surgical subspecialty. While this is a perfectly valid and, as outlined in the literature, a successful approach to changing these services – healthcare providers can be more ambitious by looking at such interventions at a hospital level (i.e. a geriatric liaison service that works across all suitable surgical services) and importantly, at ICS/whole system level. There is a clear need to develop patient pathways that encourage a shared responsibility for patient assessment, across the wider care system, and to recognise the steps that can be taken in primary care to optimise patients before procedures, such as weight management or smoking cessation.

Summary

The key steps required for successful implementation of new patient pathways include:

- Understanding your current pathways – including what works well, and what current challenges and pressures services are facing

- Establishing the future vision for services from key stakeholders

- Providing an evidence-based approach to service redesign – with data analytics and modelling to ensure pathways will adequately support the future demands placed on providers

With a growing need for healthcare services from a increasingly aging population, it is essential that our health systems have the appropriate care pathways that best fit, and respond to the complex needs presented by this cohort of patients. While the reduction in bed days and the potential associated savings alone make it incredibly difficult to make an argument against implementing such a service, it is the proven improvement in patient outcomes which sits at the heart of the case for optimising surgical pathways for elderly and frail patients.

About the author

Jordan Pilipavicius is a Consultant in Strategic Advisory. Drawing on his previous experience as a medical doctor working in secondary care, he takes a patient-centred approach to developing solutions that meet the requirements of clients across the healthcare sector.

References

- NHS Digital. Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2021-22 [Internet]. 2022 Sep [cited 2023 May 25]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-admitted-patient-care-activity/2021-22#top

- Office for National Statistics (UK). Voices of our ageing population: Living longer lives [Internet]. Census 2021: Data and Analysis from Census 2021. 2022 [cited 2023 May 25]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplep....

- Shipway D, Koizia L, Winterkorn N, Fertleman M, Ziprin P, Moorthy K. Embedded geriatric surgical liaison is associated with reduced inpatient length of stay in older patients admitted for gastrointestinal surgery. Future Healthc J [Internet]. 2018 Jun 1;5(2):108. Available from: http://www.rcpjournals.org/content/5/2/108.abstract

- Braude P, Goodman A, Elias T, Babic-Illman G, Challacombe B, Harari D, et al. Evaluation and establishment of a ward-based geriatric liaison service for older urological surgical patients: Proactive care of Older People undergoing Surgery (POPS)-Urology. BJU Int [Internet]. 2017 Jul 1;120(1):123–9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13526

- Loyd C, Markland AD, Zhang Y, Fowler M, Harper S, Wright NC, et al. Prevalence of Hospital-Associated Disability in Older Adults: A Meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1;21(4):455-461.e5. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2019.09.015

- Fowler AJ, Abbott TEF, Prowle J, Pearse RM. Age of patients undergoing surgery. British Journal of Surgery [Internet]. 2019 Jul 1;106(8):1012–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11148

- The Centre for Perioperative Care (CPOC), British Geriatrics Society (BGS). Guideline for Perioperative Care for People Living with Frailty Undergoing Elective and Emergency Surgery [Internet]. 2021 Sep [cited 2023 May 25]. Available from: https://cpoc.org.uk/guidelines-resources-guidelines/perioperative-care-people-living-frailty

- Lin HS, Watts JN, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr [Internet]. 2016;16(1):157. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0329-8

- Macmillan Cancer Support, NIHR: Cancer and Nutrition Collaboration, Royal College of Anaesthetists. Principles and guidance for prehabilitation within the management and support of people with cancer [Internet]. 2020 Nov [cited 2023 May 25]. Available from: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/news-and-resources/guides/principles-and-guidance-for-prehabilitation

- Scottish Government. Key Principles for Implementing Cancer Prehabilitation across Scotland [Internet]. 2022 Apr [cited 2023 May 25]. Available from: https://www.prehab.nhs.scot/fo...(1–4)