From managing demand to driving efficient integrated solutions

How can Ireland effectively address its most pressing healthcare challenges and steer itself towards a more sustainable and integrated future? Conor Ellis explores how population growth and changing demography must give rise to a 'twin-track' approach to investment in order to improve funding efficiency and create better health outcomes.

Nearly all societies are facing a number of challenges in healthcare delivery; demand, finance, governance, staff and patient expectation and how to improve system flow. Ireland is no different. With the appointment of regional Executives, the aim is now to guide the sometimes-disparate parts of the health and social care system into alignment behind integrated care to deliver the Sláintecare agenda, against a backdrop of unprecedented population growth and escalating healthcare demand.

With significant growth in the last decade, 2021 saw Ireland’s population surpass five million for the first time since 1851; an 8% overall increase since the previous 2016 census.[1] Moreover, population growth is predicted to continue, rising to 5.6 million in 2030.[2] This will not be fuelled by increasing births in the short term, but will instead be driven by a disproportionate increase in the number of individuals over 65; a cohort which is expected to reach c.1.6 million by 2051.[3]

The well-publicised impact on healthcare ranges from Primary Care staffing and appointment shortages, to growing waiting lists for diagnostics and elective care and record levels of public demand for treatment through hospital Emergency Departments.

Since supply is the traditional antidote to demand, an increase in resources has sought to match the relentless pace; from extra beds prioritised in the winter plan of 2020 to funding for new surgical hubs and plans which are underway for regional elective hospitals in the next three years or so. Efforts to grow the volume of physical infrastructure have also been supported by an increase in 25,000 staff over the past 3 years to 2020, of which c.57% were clinical appointments.[4]

And then there’s the rapidly rising cost of delivery. In 2024, a record €22.5 billion cash budget will be allocated to healthcare, but still the additional €708m annual allocation is only a third of the €2bn sought by the Department of Health to deliver the service. Consequently, the 2024 service plan will include – for the first time - a ‘built-in deficit’, which could be significant.

The investment conundrum

The 2002 report by Derek Wanless[5] broke new ground through its systematic demand-based examination and assessment of the resources required to provide high-quality health services in the future. Importantly, it illustrated the considerable difference in expected costs for healthcare depending upon how well people became fully engaged with the management of their own health. But even under a ‘fully engaged’ scenario, the recommended health and social care investment represents a significant increase in real terms investment as a percentage of GDP over a sustained period. Professors Charlesworth and Johnson, reviewing Wanless, outlined the trajectory arguing “…without average growth in public spending on health of at least 4% per year in real terms, there is a real risk of degradation… reductions in coverage of benefits, increased inequalities, and increased reliance on private financing. A similar, if not higher, level of growth in public spending on social care is needed to provide high standards of care…”[6]

The difficulty is that continuously increasing investment in healthcare delivery and high average “medical inflation” makes for significant public expenditure commitments and a requirement which demands unsustainable levels of investment in health as a proportion of GDP. EU commission statistics show Government-only increases of an additional 2.2% GDP between 1995 and 2021 alone, taking healthcare investment to a European average of more than 8% of GDP.[7] And while the COVID-19 pandemic prompted significant, albeit reactive increases in health investment by most Governments it simply highlighted the major deficiencies in both capacity plus resilience of our health and care systems. Many countries largely do not want to maintain this level of investment at such levels, much less the rates suggested by Wanless.

All this serves to highlight the urgent need for a renewed approach. Mounting effective responses to significant population shifts reinforces the need for a relentless focus on savings, consolidation and maximising efficiencies if we are to achieve a model of funding and operation which is sustainable in the longer term.

The difficulty is that continuously increasing investment in healthcare delivery and high average “medical inflation” makes for significant public expenditure commitments and a requirement which demands unsustainable levels of investment in health as a proportion of GDP.

Spotlighting service transformation

There are numerous long-term, strategic initiatives which are already under way which are serving to inject excellence, value and embed long-term solutions into the Irish Health System. The commencement of the Department of Health’s Productivity and Savings Taskforce will make a real call for improved efficiency within the system, while long-term programmes of change and improvement within HSE will develop a system of more integrated care and support the left shift of services.

But in the shorter term, there are also a wide variety of pragmatic, cost effective interventions which can significantly impact the efficiency of existing services, ranging from remote or virtual care, community rehab teams and system alignment through Target Operating Models to better value from estates by enhanced bed space audit techniques. Whilst some have undoubtedly been realised through investment in new technology or buildings, many are simple changes which have improved the way providers and healthcare organisations collaborate.

In this quick reference guide, we have summarised some of our own work in identifying and implementing evidence-based interventions for health systems and providers, alongside a range of other case studies where a focus on change, not capacity, has delivered significant value to the health economy in terms of performance, experience and outcomes. These examples have been selected from a continuously growing library of more than 120 global case studies which our team have created to demonstrate and learn from the broad range of opportunities in this space.

After all, the fact is that a considerable proportion of the patients we find in hospital beds, are not in the right place. A recent Dutch study showed a range of between 14-35% of patients and several others have evidenced c.20% of all acute beds are occupied by patients who are not in need of acute care.[8]

Emergency Departments are meant as places to deal with complex and difficult cases. As far back as 2007 the International Association of Emergency Managers offered their support to the concept of Urgent care centres.[9]

Whilst all areas have differing needs, it’s about the levers that can contain the SDEC, Frailty, social care and urgent - not emergency - cases that can halt the onward direction of ever larger ED floorplates. Notable work has gone into admission avoidance and in one case in the north east of England (Sunderland) the organisations have invested in driving integrated care packages, taking 15% of attendances out of the local ED (over a 10 year period), through collaboration of all stakeholders.

In the shorter term, there are also a wide variety of pragmatic, cost effective interventions which can significantly impact the efficiency of existing services, ranging from remote or virtual care, community rehab teams and system alignment through Target Operating Models to better value from estates by enhanced bed space audit techniques.

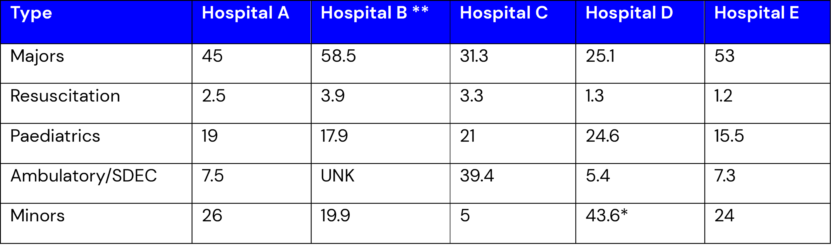

The table below shows 5 different Emergency Department (ED) caseloads as a percentage of total admissions; four in the U.K. and one in Ireland and all similar sized conurbations.

*Includes assessment area ** excludes UNK SDEC impact

One of the UK hospitals has access north and south in the area to two urgent care centres, and whilst this is certainly not empirical evidence - since one needs to consider how health organisations treat caseload - it is interesting that the range of ambulatory is far lower than most of the other facilities as a % basis. Hospital B data for SDEC was not available but is expected to become a sizeable part of the diversion away from the main ED. Other hospitals we have worked with have a range of minor caseload, mostly similar to those in the table but some up to and beyond 50% of attendances. Some of these can fit into UCC scenarios. The RCOP paper in 2022 compared approaches to SDEC and is a good read with practical examples of change. It notes that a clear definition and comparator approach is still some way off.[10] The emphasis on achieving anywhere near the 30%+ SDEC deflection away from ED that some commentators think could work, would surely also impact on positively on relieving some clinical time. This should also reduce unnecessary admissions as a by-product, and in doing so free up senior staff for more complex cases.

This is just one part of the journey alongside discharge and rehab that makes approaches to embracing integrated care the pre-requisite. Investment in the capacity and quality of social care is a leading part of the equation, enabling the focus for acute settings to be placed on delivering more complex and expensive care, in the right place for those who require these services.

Ireland does need significant extra beds, but it also needs some system reform through implementing a twin-track approach.

Yes, the demography of our communities is irrefutably changing, but while Ireland indeed has some regional pockets of considerable ageing, the average age remains a fairly ‘youthful’ c.38 years in comparison to many other European countries[11], with concentrations of younger cohorts who may be more able and willing to embrace alternative models of care and self-management techniques and help reduce pressure in the system. Take Asia, where the over 65s population is fast heading towards 500m by 2027 and will represent over 60% of the global over 65s cohort by c2030[12]; a formidable challenge for healthcare provision. Yet they also recognise the opportunities which might be leveraged from having a youth population who are arguably at the vanguard of healthier lifestyles and digital technology, including data driven health wearables and use of other smart technologies.

Ireland does need significant extra beds, but it also needs some system reform through implementing a twin-track approach.

A framework for change

There is no ‘silver bullet’ to achieving the level of service improvement required.

The opportunities for new interventions do not discount the need for proper levels of ongoing real-term investment in our health systems, nor the need for a staunch defence of capital budgets which are too often raided to plug financial gaps. However, by looking toward local, national and international best practice we can draw upon successes which guide us towards interventions which achieve meaningful impact and by working across conurbations, in the way both Manchester and Glasgow have managed, all at the fraction of the cost of additional acute bed stays.

Sláintecare has set the framework and vision for change in the way we deliver care. The key is in making best use of analytics, drawing on both existing and comparative data to interpret our future sense of right performance, right location and addressing the Ireland of 2040 from a population perspective. In doing so we need to address how we achieve more integrated collaborative working across health boundaries by looking at lessons learn globally for integrated health models. By sharing and implementing targeted and pragmatic best practices and working collaboratively, we can ensure investment meets not only the short-term imperatives of more beds, greater diagnostic and elective care, but also address step down care, social care, primary and mental health as a system-wide care continuum.

For more insight and guidance on healthcare in Ireland, get in touch with Conor Ellis.

References

[1] Demography - CSO - Central Statistics Office

[2] Population of Ireland 2030 - PopulationPyramid.net

[3] Population Projections Results - CSO - Central Statistics Office

[4] gov - Health Minister announces establishment of Productivity and Savings Taskforce (www.gov.ie)

[5] 20210611_Revisiting_the_Wanless_review_PDF.pdf (health.org.uk)

[6] What is the right level of spending needed for health and care in the UK? - The Lancet

[7] Government expenditure on health - Statistics Explained (europa.eu)

[8] Leaving the hospital on time: hospital bed utilization and reasons for discharge delay in the Netherlands | International Journal for Quality in Health Care | Oxford Academic (oup.com)

[9] IAEM Position Paper on Urgent Care Centres 22.01.07.doc

[10] clinmed.2021-0614.full.pdf

[11] Inforegio - EU population projections reveal growing gaps between young and old (europa.eu)

[12] Ageing and Wellness in Asia (adb.org)