The counter-intuitive case for disinvestment in the NHS Estate

Malcolm Lowe-Lauri and Dr Rachel Hampson FRICS discuss the increasing risks arising from backlog maintenance across the NHS estate, and how effective planning for disinvestment may form part of the solution.

The condition of the NHS’s estate is in many cases poor and getting worse. While workforce strikes have caused significant disruption to procedures of late, the number of procedures cancelled or delayed due to infrastructure failure is a far greater, reoccurring and increasing statistic every year which puts understandable emphasis on what we can build to solve the problem, and how quickly.

Much of this is highlighted in the recent NHS Providers report, “No more sticking plasters”, which notes the opportunity for recapitalisation to improve productivity and performance and welcomes the recent increase in capital available through the multi-year approach in the most recent Spending Review. However, it also observes that the increase tails off in the later part of this decade and reminds us that, in difficult revenue times, capital budgets are at regular risk from raiding in to support the revenue position.

Meanwhile, NHS England’s (NHSE) New Hospital Programme (NHP) has taken a fair bit of criticism as a major programme of capital investment. Some of this is inevitable after decades of underinvestment in NHS estate, especially since it is competing with other government departments for capital rather than funding at a local and project level as was seen through private finance initiatives (PFI). At the same time, it has perhaps struggled to convince some of its objectives – standardising hospital building practice, getting the best commercial deals for the taxpayer, articulating transformational care models (which arrived a bit later), fixing the estate problems that represent a danger to staff, visitors and patients.

Any investment of capital at scale as promised by NHP is to be welcomed. However, we should recognise that even if all 40 hospitals were to be successfully built this will still not address the level of investment required in the NHS estate to adequately reduce the serious and significant risk that exists. Nor will it help address the system-wide challenges facing urgent and emergency care, cancer and elective backlogs, and the much-needed support for a depleted, weary and frustrated workforce.

The state of the estate

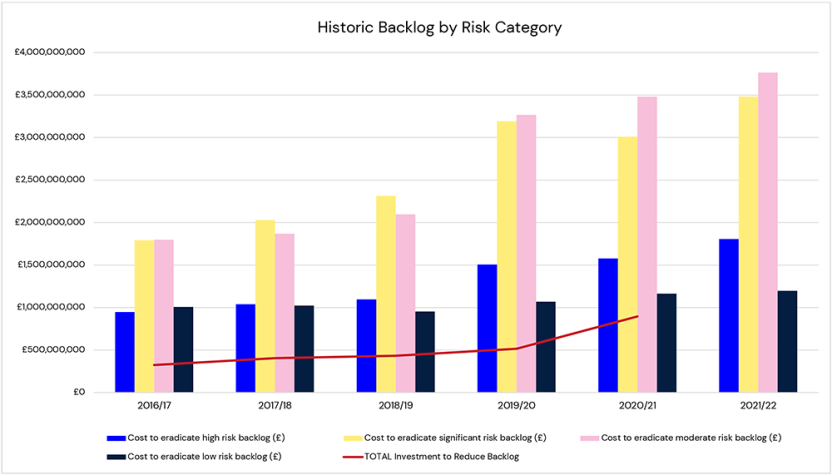

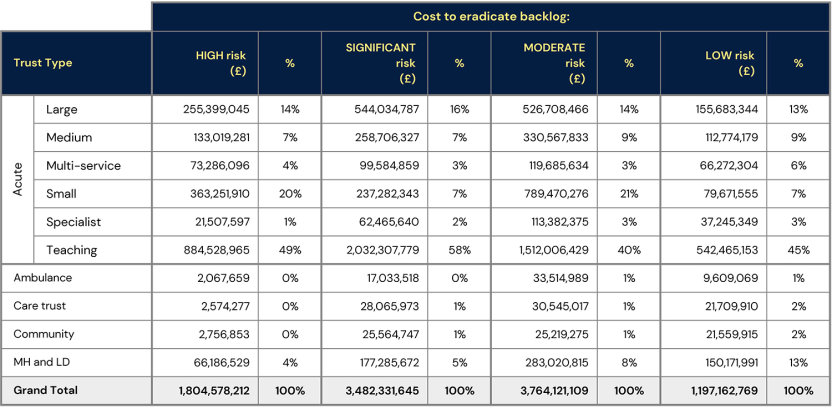

We are currently fighting something of a losing battle in reducing backlog maintenance. The figures below show this over the last six years of Estates Returns Information Collection (ERIC) returns where the data shows high and significant risk elimination costs are increasing annually.

Interestingly, when broken down by hospital type there was initially no clear match between where the challenge is greatest and the hospitals on the NHP list, although arguably the more recent addition of the reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) hospitals provides some rebalancing in this respect.

If we were to direct investment according to this data, available funding would be prioritised for the acute teaching trusts, whose significant risk backlog represents well over half of the total across the estate. Yet the deeply concerning risks posed by RAAC affected hospitals are firmly in the public spotlight, with the costs of their replacement or refurbishment likely to exceed £2.5bn alone. Likewise, the data regarding service failures does not make for happy reading.

Recent press paints a more vivid picture of the problem; sewage leaking on to cancer wards, maternity units and A&E departments, into hospital rooms and on to general wards.

Taking the NHS’s capital history and its current financial predicament, achieving sufficient investment to address the increasing number of issues across the estate is highly unlikely. Instead, could planning for disinvestment form part of the solution?

Planning for disinvestment

At an Integrated Care Board (ICB) level, an unequivocal safety and quality lens should be taken to the estate, considering the following questions:

- Can our high and significant risk estate be brought up to Condition B (a level of building condition defined by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors as being ‘sound, operationally safe, and exhibiting only minor deterioration') and how quickly?

- If remediation is not possible can we repurpose the relevant parts of the facility e.g. for lower acuity use?

- Could it be available to alternative but related provision e.g. for social care?

- If repurposing is not possible can we isolate and mothball the space?

There is a lot of estate built in a standardised way in previous investment programmes such as Nucleus builds that could be repurposed. This is a low cost – high reward opportunity with a particular generation of hospital buildings. The learning should be applicable to other health facilities.

When implementing alternative use or disposal, there are inevitable consequences for operational delivery which need to be quantified. Many experienced estates and facilities teams have contingencies to address deteriorating spaces. Do the same contingencies exist for service delivery? In many cases the sheer need to use anything available e.g., for the overspill of emergency services, will have made this difficult. There are some promising initiatives either in preparation (diagnostic centres, treatment hubs) or in operation (virtual wards) which will make a difference. Although there will continue to be questions raised about where the workforce will come from, and how (in terms of diagnostic centres) they will help manage demand rather than increase supply.

While there is clearly variation across ICBs and providers in the nature and extent of improvement and transformation implementation, there is no doubt that a combination of both will be needed to bridge the facility gap and reconcile the need to prepare for disinvestment while meeting increasing demand and securing safety and quality at the same time.

Transformation and improvement - opportunities and considerations

From emergency care improvement support team (ECIST) work it is clear there are still significant opportunities to improve urgent care flow although the ability (and inability) to control outflow into social care, which needs to be factored in.

We know from getting-it-right-first-time (GIRFT) analysis and the recent elective recovery programme planning there are opportunities to generate greater volumes of activity and to reduce the inflow of referrals e.g., with robust pre-hospital musculoskeletal (MSK) services.

We see the development of artificial intelligence (AI) tools which can cut the number of patients waiting for cancer diagnosis through identification of those who definitely do not have cancer (and resolve a lot of patient anxiety in the process).

The development of predictive analysis and early intervention, especially in mature systems, is increasing the degree of control over urgent and emergency care and can arrest the onset of long-term conditions, as in the work of the Leicester Diabetes Centre.

The emergence of broader digital platforms is connecting services across the ICB and supporting a distribution of activity to different parts of the system, helping patients take a lot more control of their health monitoring and maintenance.

Drawing on these examples and other local initiatives each ICB needs to understand and consider:

- What is the extent of its estate exposure as per questions i)-iv), above?

- What would disinvestment do to the ICB performance requirements?

- What improvement and transformation potential does the ICB have to bridge the deficit and over what timescale?

- How does it factor these considerations into its population planning responsibility?

- How is this articulated in the estates and infrastructure strategies of ICBs and ICPs, so that estate planning, service planning, safety and quality are properly brought together?

- How does it link this to disinvestment business case preparation and related issues such as land and property disposal and capital receipts?

Leaders are reminded that the workforce should be given a key role in planning, as well as delivery. From our work on clinical strategy and remodelling clinical services we have observed that clinical stewardship of key challenges is able to unlock fresh thinking and ingenuity. We see some great work in progress, such as Cambridge University Hospitals redistributing clinical responsibility to drive down patient waits, and Swansea Bay Health Board developing the relationship between primary and secondary care to support early, non-hospital intervention. There are many other local initiatives, but the key is to create the environment for these to emerge from clinical conversations.

The challenges facing the NHS estate have been caused by historical underinvestment, but the size of the problem has gone beyond even an optimistic outlook for capital financing as the solution. If we continue to attempt remediation through investment, we will be left no choice but to accept high and significant risk one way or another. We simply cannot allow ourselves to become inured to ongoing risk and service failures. Planning for disinvestment is now a necessity to ensure the safety and performance of the future NHS estate.

Archus have developed a full set of disinvestment appraisal criteria which covers healthcare planning and demographics, finance, building status, Estates & Facilities Management, Net Zero Carbon/Decarbonisation.

To start a conversation regarding the benefits, opportunities and successful approaches for disinvestment, please get in touch.